At Syriza’s HQ, the cigarette smoke in the cafe swirls into shapes. If those could reflect the images in the minds of the men hunched over their black coffees, they would probably be the faces of Che Guevara, or Aris Velouchiotis, the second world war Greek resistance fighter. These are veteran leftists who expected to end their days as professors of such esoteric subjects as development economics, human rights law and who killed who in the civil war. Instead, they are on the brink of power.

Black coffee and hard pretzels are all the cafe provides, together with the possibility of contracting lung cancer. But on the eve of the vote, I found its occupants confident, if bemused.

However, Syriza HQ is not the place to learn about radicalisation. The fact that a party with a “central committee” even got close to power has nothing to do with a sudden swing to Marxism in the Greek psyche. It is, instead, testimony to three things: the strategic crisis of the eurozone, the determination of the Greek elite to cling to systemic corruption, and a new way of thinking among the young.

Of these, the eurozone’s crisis is easiest to understand – because its consequences can be read so easily in the macroeconomic figures. The IMF predicted Greece would grow as the result of its aid package in 2010. Instead, the economy has shrunk by 25%. Wages are down by the same amount. Youth unemployment stands at 60% – and that is among those who are still in the country.

So the economic collapse – about which all Greeks, both right and leftwing, are bitter – is not just seen as a material collapse. It demonstrated complete myopia among the European policy elite. In all of drama and comedy there is no figure more laughable as a rich man who does not know what he is doing. For the past four years the troika – the European Commission, IMF and European Central Bank – has provided Greeks with just such a spectacle.

As for the Greek oligarchs, their misrule long predates the crisis. These are not only the famous shipping magnates, whose industry pays no tax, but the bosses of energy and construction groups and football clubs. As one eminent Greek economist told me last week: “These guys have avoided paying tax through the Metaxas dictatorship, the Nazi occupation, a civil war and a military junta.” They had no intention of paying taxes as the troika began demanding Greece balance the books after 2010, which is why the burden fell on those Greeks trapped in the PAYE system – a workforce of 3.5 million that fell during the crisis to just 2.5 million.

The oligarchs allowed the Greek state to become a battleground of conflicting interests. As Yiannis Palaiologos, a Greek journalist, put it in his recent book on the crisis, there is “a pervasive irresponsibility, a sense that no one is in charge, no one is willing or able to act as a custodian of the common good”.

But their most corrosive impact is on the layers of society beneath them. “There goes X,” Greeks say to each other as the rich walk to their tables in trendy bars. “He is controlling Y in parliament and having an affair with Z.” It’s like a soap opera, but for real, and too many Greeks are deferentially mesmerised by it.

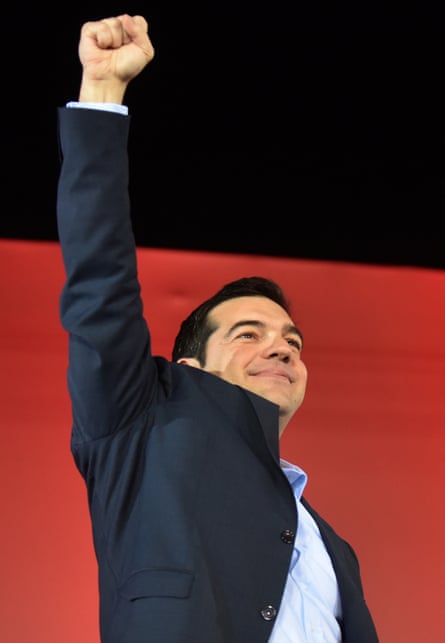

Over three general elections Syriza’s achievement has been to politicise the issue of the oligarchy. The Greek word for them is “the entangled” – and they were, above all, entangled in the centrist political duopoly. Because Syriza owes them nothing, its leader, Alexis Tsipras, was able to give the issue of corruption and tax evasion both rhetorical barrels – and this resonated massively among the young.

And here’s why. In a functional market economy, the classic couple in a posh restaurant are young and close in age. In my travels through the eurocrisis – from Dublin to Athens – I have noticed that the classic couple in a dysfunctional economy is a grey-haired man with a twentysomething woman. It becomes a story of old men with oligarchic power flaunting their wealth and influence without opprobrium.

The youth are usurped when oligarchy, corruption and elite politics stifle meritocracy. The sudden emergence of small centrist parties led by charismatic young professionals in Greece is testimony that this generation has had enough. But by the time they got their act together, Tsipras was already there.

From outside, Greece looks like a giant negative: but what lies beneath the rise of the radical left is the emergence of positive new values – among a layer of young people much wider than Syriza’s natural support base. These are the classic values of the networked generation: self-reliance, creativity, the willingness to treat life as a social experiment, a global outlook.

When Golden Dawn emerged as a frightening, violent neo-Nazi force, with – at one point – 14% support, what struck the networked youth was how many of the political elite pandered to it. People who had read its history could see a replay of late Weimar flickering before their eyes: delusional Nazis feted by big businessmen craving for order.

I’ve reported the Greek crisis since it began, and what changed in 2015 was this: Syriza had already won the solid support of about 25% of voters on the issues of Europe and economics. But now a further portion of the Greek electorate, above all the young, are signalling they’ve had enough of corruption and elites.

Greece, though an outlier, has always been a signifier, too: this is what happens when modern capitalism fails. For there are inept bureaucrats and corrupt elites everywhere: only the trillions of dollars created and pumped into their nations’ economies to avoid collapse shields them from the scrutiny they have received in Greece.

We face two years of electoral uncertainty in Europe, with the far left or the hard right now vying for power in Spain, France and the Netherlands. Some are proclaiming this “the end of neoliberalism”.

I’m not sure of that. All that’s certain is that Greece shows how it could end.

Paul Mason is economics editor at Channel 4 News. Follow him @paulmasonnews